September 12, 2025

Fractals: Nature’s Healing Patterns in Design

In the 1960s, mathematician Benoît Mandelbrot began exploring a concept he initially called self-similarity—geometric forms whose parts resemble the whole. A simple example is a straight line: any segment of it is also a straight line. But this kind of geometry also appears in nature, like in the head of Romanesco broccoli. Each floret forms a spiral that mirrors the spiral arrangement of the florets on the entire head.

In 1975, Mandelbrot named this phenomenon a fractal. It turns out fractals are everywhere in nature: the way rivers branch into tributaries, or how a tree trunk grows branches, which then grow twigs. More recently, researchers have suggested that human brains recognize these fractal patterns—sometimes subconsciously—and because we associate them with nature, seeing fractals can evoke similar calming effects as being in a natural environment.

So, why discuss fractals on a podcast about sustainable architecture and design? Because fractals are common in pre-modern architecture—found in the ornaments of Gothic cathedrals and the niches of medieval mosques—and today, many designers apply fractal principles to objects and materials, creating products that evoke the same sense of well-being as natural environments.

In the latest episode of Deep Green, created in partnership with Momentum, Avi Rajagopal sits down with Dr. Richard Taylor, whose research underpins our understanding of fractal patterns’ impact, and Anastasija and Martin Lesjak of 13&9, who apply this research in their designs—including a new wallcovering collection for Momentum called Renaturation.

Avi Rajagopal: What is fractal fluency? Can you give us a quick overview of that?

Richard Taylor: Looking back in evolution over 600 million years, our visual systems have been gradually tuning themselves to the surroundings. Those surroundings have lots of examples of fractals in them. The visual system has literally become fluent in the visual language of fractals, and the brain craves to see this. When we wander away from what the brain wants to look at, that’s when all these sorts of problems to do with health and wellbeing start to emerge.

AR: But what do we mean by the fluency part of this? Aren’t we already fluent in Fractals? Isn’t it kind of wired into our brains?

RT: I think it’s a fundamental part of being a human being that we all share this heritage of needing to actually see them. For our ancestors it was not a problem because they could spend a lot of time in the forests. It’s over the last 10,000 years where, we’ve changed the way that we operate in life and we end up in these buildings. That’s when the problems start because we’re not fluent in that language that typical buildings present.

When you hang out in nature, you’re at ease because your whole body and your brain speak this language. But when you wander into a typical building, it’s like being transported to some far-off land where you don’t understand the language. Your stress levels go up immediately.

AR: Wow! Martin and Anastasija, when did you start to think about applying this idea of fractals to the way you design things?

Martin Lesjak: We started to think about biophilic design almost a decade ago. It was just at the beginning of this big movement that we have now when biophilic design is existing since a while, but only the recent years are really where it’s become so popular. We tried to bring in real nature, integrating plants, natural materials, etc. but at one point we wanted to know what is behind this romanticism of biophilia. We started to do research and one name regularly popped up, and this was professor Dr. Richard Taylor.

At one point I said, I would love to talk to this guy because I think he’s the key. We wrote an email, and this was the beginning of everything and the rest is fractal design history.

AR: Anastasija, now you’ve been applying this work in collaboration with Dr. Taylor in a lot of different ways. Tell us about your journey?

Anastasija Lesjak: The journey was amazing. I talked often to Richard. When you first start to read publications, some of the facts are kind of common for you, but there was no interface between design and science. We worked very instinctively. We had our artistic approach, but we were always very multidisciplinary. We never had long term collaboration with science and that was the game changer for us. We learned a completely different way to approach design. We educated ourselves in certain parameters that we must know about fractals. We started to think differently about build environment, integrating health and wellbeing into build environment with our product applications.

There were no more random design trials. Every step that we did was in a collaboration with Dr. Taylor and he gave us a space for our creativity because it’s kind of natural thing as well. Our eyes are also very spontaneous and artistic, and like I said, instinctive, but there is also certain a sweet spot that you have to know when you design fractals that they have a stress reducing effect. And that was also for us was something completely new.

Like Martin mentioned it been eight years, so we became friends, a team, a fractal family. We have our team back in Austria – architects, interior designer, product designer, graphic designer, sound designer, fashion designer, and a textile designer and Richard has his team at the University of Oregon at Fractals Research.

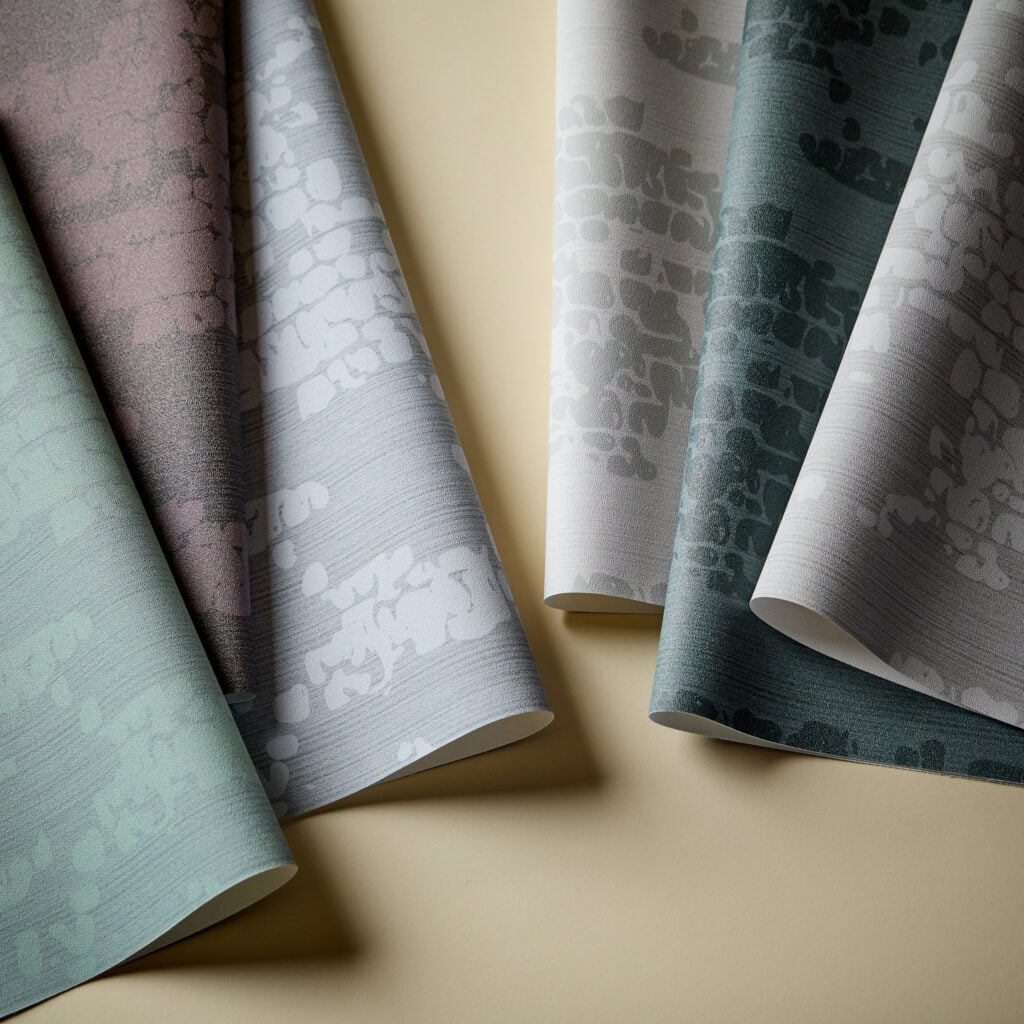

AR: I wonder if you can give us a little bit of a description of the newest baby from the Fractal family, which is “renaturation” this new collection for momentum.

ML: Renaturation is a big political discussion. We know it is, especially from the European Union. There’s a new law where 15% of agricultural or industrial landscapes need to be given back to nature. It’s similar to what we do with the built environment. We want to give it back to nature or to natural essences like fractals. In recent years, for this collection, we worked with software that we created together with Richard’s team to generate and grow these fractal patterns. With this software, we are able to control the parameters necessary from a scientific perspective to get the result of stress-reductive patterns.

With the renaturation collection, we went the opposite way. We took actual patterns from nature, morphed them, abstracted them, and treated them until we hit the sweet spot where they had these stress-reductive properties. When we created an embed, and Richard and his team did the testing.

But the outcome, from an aesthetic perspective is something completely new compared to the ones before. They’re super organic and even more natural than the computer-generated ones. For example, we have three patterns: the river, the bark, and the moss. The moss looks like real moss growing out of concrete walls when they’re in the shadow, developing that greenish pattern over time. The river looks like an aerial view of a river system, and the bark really captures the texture of real bark that we took but then abstracted in a very sophisticated way to match all the manufacturing criteria, application criteria, and scientific properties.

AR: What are you optimizing for? How do you optimize the patterns?

RT: You may think, why don’t we just take a photograph and just put it on a wall?

The first thing is that, when you wander through a forest that’s a great experience and it’s fundamentally a different environment when you’re walking down a corridor of an airport. Imagine, if we were putting one of these designs on the walls of the airport, the floor and the ceiling are relatively simple compared to anything that you would experience in the forest. That puts extra pressure on the walls to deliver the naturalness. The second thing is not just the environment, but what are people doing in that environment? When you’re in a building, you’re doing something very different than just wandering through a forest. We must adapt things for that as well. The third thing is who is the person? Neurodiversity, not everybody is the same. We have to consider the occupant.

What is special about the fractal pattern in the built environment is all these repeating patterns. What that does is build up an immense visual complexity, and that’s what your visual system craves. So, when you walk into the built environment, which is much simpler, you don’t get that complexity, but we have to tune that complexity in based on the environment that we’re putting it in.

AR: Anastasija, you mentioned changing your design approach. What does this collection teach us about product development for the building beyond just the product itself?

AL: You want to understand the context and your design in this case. You don’t end up with product, you end up with a tool the designer can use, express their own creativity, dive deeper into a certain subject and maybe influence something completely different through this product. What is the added value behind this product? Each product has its own added value in material, its creation, sustainability, great manufacturing partners, the team and everything that we create together. But beyond that, there is no story to end. It doesn’t end just with one product, to me it always has a larger context.

RT: Absolutely. Yeah! It would be awful if there was just one fractal design that had to appear everywhere. But there isn’t, with our tool, there’s lots of opportunities to create lots of superficial differences in the design and as long as you get that complexity right, it will trigger these massive stress reductions.

AR: This is incredible! One of the things that makes it work is because you’ve actually figured out a way of measuring this impact. You call it Devalue. Tell me what devalue is?

RT: Yeah. We mentioned earlier that one of the special things about a fractal is its visual complexity, but there are many different fractals out there and some are more complex than others. The way that we quantify that complexity is that we introduce this term called fractal dimension, but we simplify it and just call it the D-value . What it’s doing is charting the complexity on a scale between one and two. The closer to one, the simpler the fractal, and if it is closer to two, the more complex.

The key aspect of our stories is that the most prevalent fractals in nature are complex—those are the ones we’ve become fluent in. We’re making sure that when we are designing, we have that level of complexity to it. Exposing people to these fractals triggers immediate relaxation and boosts cognition. When designing patterns for momentum, that’s our goal. Unlike artificial shapes, where you choose between relaxation or stimulation, fractals—refined over 600 million years—can do both simultaneously. When we’re choosing this devaluation, we decide the balance of relaxation and stimulation. For momentum patterns, we have a slightly higher devaluation because we aim not just to relax but also to engage throughout.

AR: That’s what I love about this collection.

Listen to the full “Fractals: Nature’s Healing Patterns in Design” episode on the Surround Podcast Network.

Latest

Projects

Where Housing Meets Humanity

Three innovative housing projects that focus on care, community, and climate, redefining public housing with dignity.

Projects

Jeanne Gang on Harvard’s New Rubenstein Treehouse

The architect unpacks how material, structure, and openness converge in the university’s first mass timber building.